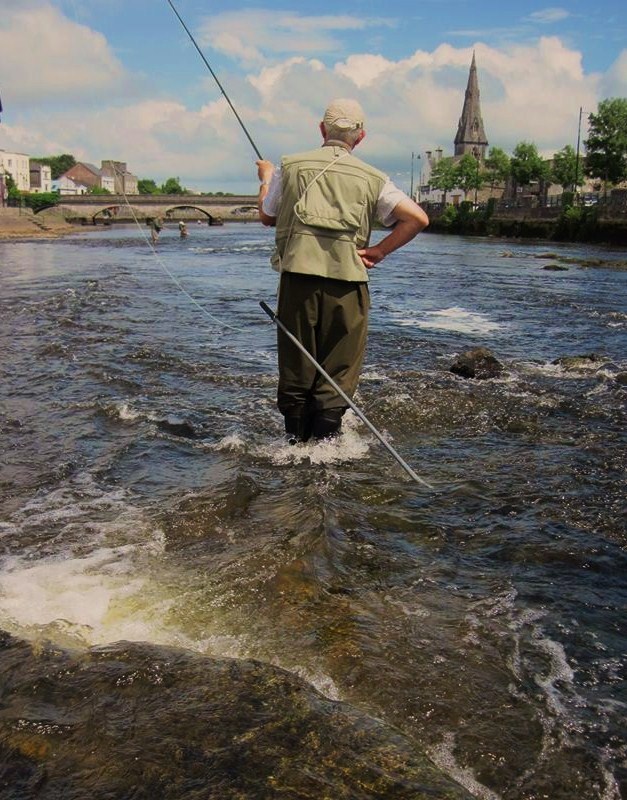

Marko Feltes playing a salmon on the river Moy

HOOKING SALMON ON THE FLY(part 1)

If there is one aspect of salmon fly fishing technique that causes frequent frustration, spoiled holidays, frayed tempers, and missed opportunities then it must be the inability to properly hook the fish that take our flies. There are many reasons why this lack of what is basically a simple technique should be so prevalent, and one of the main culprits is conflicting information in angling books, or sources such as some internet fishing websites/forums. Fishing forums are occasionally the source of confusion and unsound advice as some of the persons offering advice in their posts are inexperienced but this does not stop them offering their wisdom to all, even though they may have personally caught few salmon. The inexperienced contributors to these forums don’t fully realise the inadequacy of their experience and to be fair they probably think that they are helping some other beginner along the way. The new visitor posting on some of these forums looking for advice will usually get some very good advice from one or more of the really experienced members, but he or she may also get many other replies from novice anglers, so which advice should be taken? . Well the reality is that he or she will not usually know which advice is good and which is unsound as there will be so many conflicting opinions offered and the good advice often gets lost among all the various contributions. The old boy’s years ago used to say that one shouldn’t be giving advice on salmon fishing to anyone until they had landed at least five hundred fish and better still to wait until after they had landed a few thousand. When an angler has landed about five hundred salmon you can say that he or she has acquired a reasonable or good level of experience and when that figure increases to a couple of thousand or more then one can be sure that a high level of skill and experience has been achieved. The key word in all this is experience. In an earlier article we looked at the creation of a vulnerable prey image as been the most important thing of all, but actual fishing experience built up over a number of years is also very important.

A total beginner can cast his fly haphazardly across the stream and by pure chance actually create a good presentation, and if by chance there happens to be a taking fish near the fly it may rise and take. Our beginner then strikes immediately, hooking his first salmon eventually landing it, and then fishes on for the rest of the day without another take. In this case our beginner was lucky that his haphazard presentation still created an attractive image, and that luckily there was a taking fish in the vicinity, with the final bit of luck being that despite striking too soon he still managed to hook his fish. Let’s put our experienced angler into the same scenario and look at what might happen. Our experienced angler makes a cast that lands in a similar fashion to our beginners cast and immediately realizes that his line hasn’t lain out on the water as he had planned, but rather than cause extra disturbance through recasting he lets his fly fish around. The salmon rises and takes the fly while our experienced angler doesn’t strike immediately but allows adequate time for the fish to take properly hooking the fish and eventually lands it. The experienced angler was fully aware that his line had landed in a mess or at a different angle across the stream than he had originally intended but he let his fly fish around as it was still fishing reasonably well. After getting a take at that angle of presentation the experienced angler had a little review of the situation,and his strategy. Maybe the current here is slightly slower/faster than first calculations suggested, and maybe it might be a good idea to continue with this angle of presentation. He then proceeds to hook two other salmon in the pool, landing both as his hooking technique had been perfected over many years. For the beginner luck played a major role, but for the experienced angler it was his well practiced keen observation that allowed him to realize what had actually transpired and to take maximum advantage.

A lot of effort to get into position and hopefully a calm reaction when the fish takes

Luck is of course a factor in salmon fishing, but for experienced anglers the luck that is most important is to be in the right place at the right time, and when a salmon takes their fly they will successfully hook the majority of them. Experienced anglers that hook a high percentage of the salmon that take their flies have either been taught a correct hooking procedure or through trial/error, and the heartache of many lost fish have developed a style that definitely does not include any form of rapid lifting or striking as the fish is in the process of taking. I have used the word process, as this is the best description of what may happen or develop when a salmon takes. This process maybe over in a split second or it might take anything up to ten seconds to complete, and this is all very normal as salmon can come to take our flies in many different ways.

A salmon may take our fly in a variety of ways such as, take in arcing movement and then continue to circle right or left back downriver from us, take and back directly downstream for a considerable distance before turning, take and then continue forward a little before either turning or just gradually tail back as it returns to the river bed, suck in the fly and hold station whilst shaking its head savagely eventually turning left or right back downriver, Bow wave directly to the fly from some distance and take with a dramatic swirl, among others. With such wide scope for individualistic taking behavior in certain situations it is obvious that no one hooking technique will be one hundred per cent successful all the time, even the correct application of two or three well adapted hooking techniques for various situations when used wisely still wont give us perfection, but then why should it? salmon are wild creatures and we are after all only human. The real question should be-what hooking technique works best most of the time?

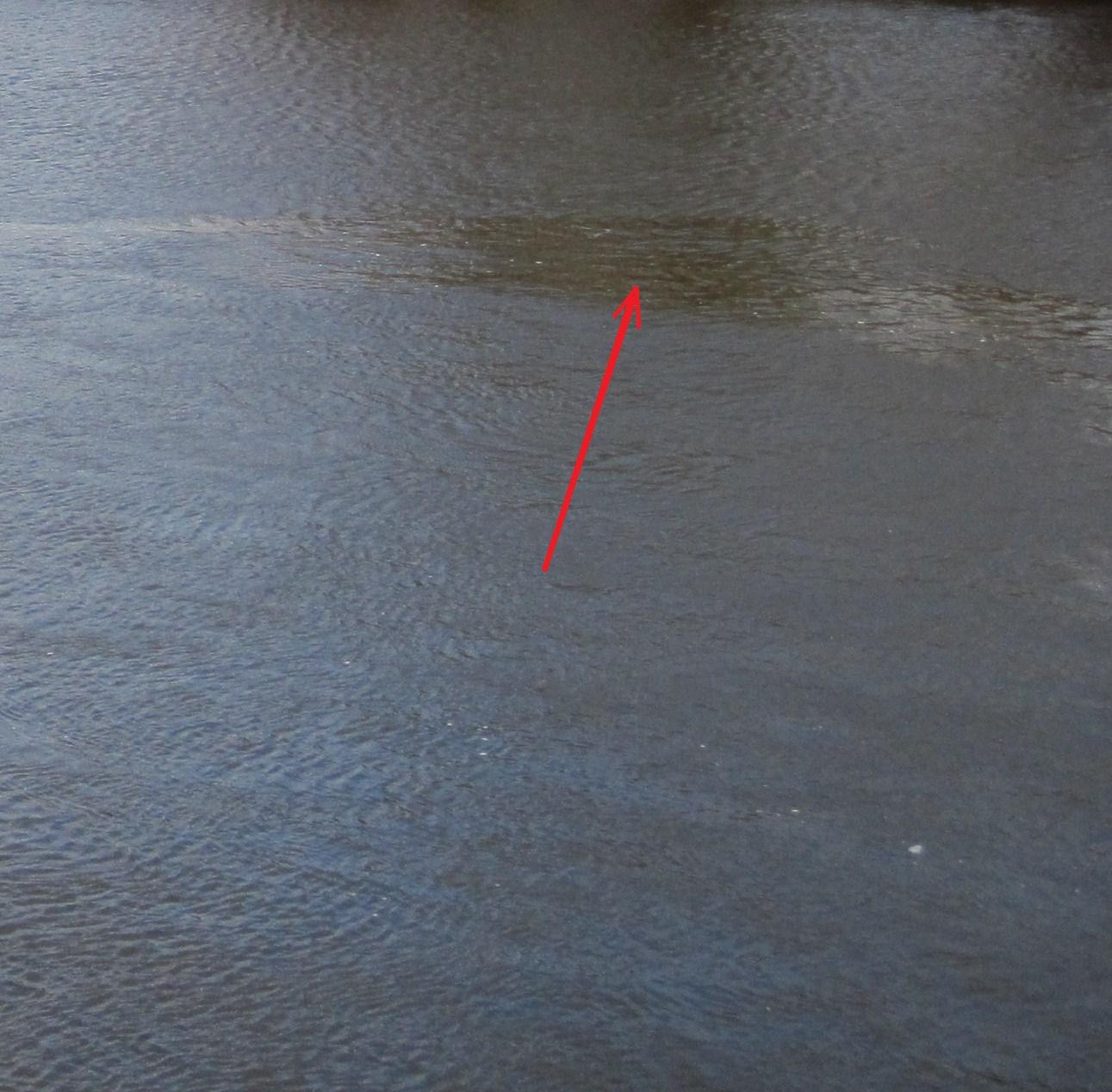

A high rod tip provides a nice shock absorbing droop of fly line

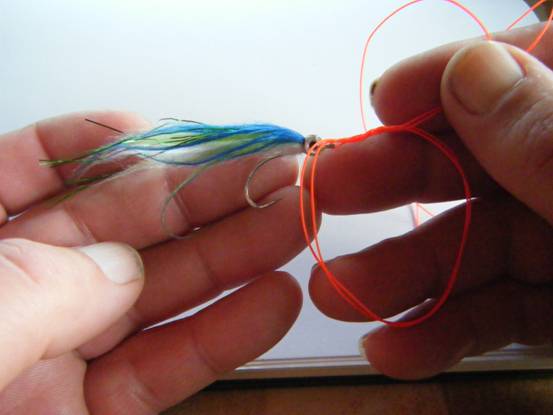

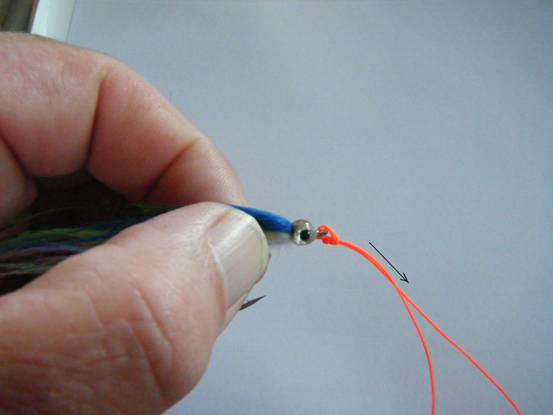

The hooking technique that I use for the vast majority of my fishing is very straightforward and easy to execute. I was shown this style by the late Tommy Byrne from Swinford when I was teenager and it has worked well for every angler I have passed it on to since. While my fly is swimming across the river I keep the rod tip well up and by this I mean the rod should be held up at least at 45 degrees if possible. This creates a drooping curve of fly line from the rod tip to the water acting as a shock absorber against sudden takes and also it acts as a visual indicator of a developing take as the fish pulls line starting to straighten this curve. We will often see the take with this visual aid even before we start to feel the take at hand. The actual initial feel of the take at hand can vary from the sensation of the fly line feeling almost imperceptibly slightly heavier right up to the slamming take that warps the rod around and the fish taking line off the reel immediately. The majority of takes start with a tap or a tug, this can follow a variety of sequences such as, tug tug, tug nothing for a couple of seconds then tug tug, three or four fairly evenly spaced tugs that develop into stronger pulls, the important thing is that if we give the fish enough time these tugs will get stronger and start to feel more like really positive pulls rather than taps or relatively gentle tugs. The taps or tugs are caused by the salmon shaking its head as it tries to crush and kill the prey it has captured and as the fish progressively starts to add more full body movement to this killing action the tugs get stronger eventually culminating in the salmon trying to return to its lie.

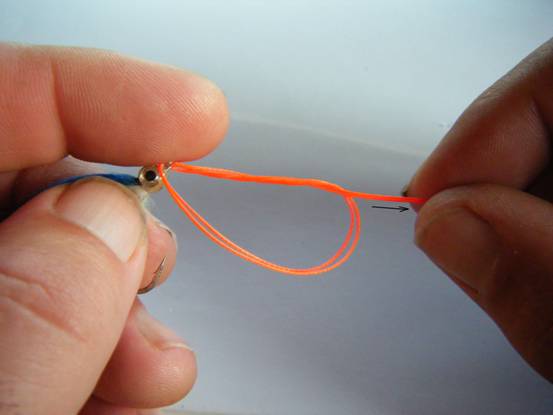

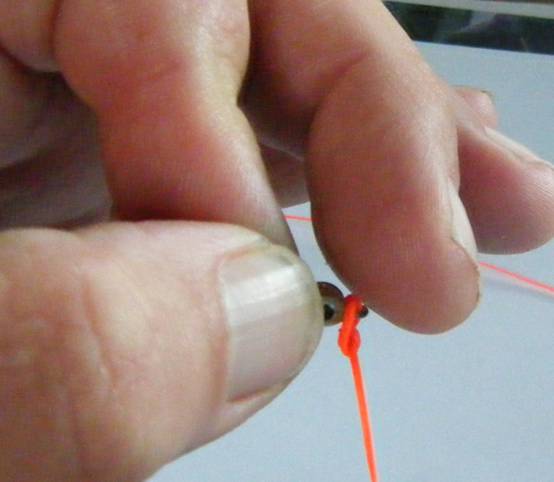

Dropping the rod tip to a taking fish

When I get the first indication of a take whether it is the line starting to straighten or a tug I drop the rod a little and wait to see what develops. I hold the rod completely still in this position until I get more tugs and then I drop my rod tip a little more. While these tugs continue to remain fairly gentle I gradually continue gradually dropping my rod tip and only stop dropping the rod when the tugs develop into really strong pulls. When the fish starts to pull strongly I clamp the fly line while calmly and progressively raising the rod back up to about 45 degrees

At this stage I have the line clamped against the weight of the fish with the rod back up at or slightly above 45 degrees and I hold everything tight for a few seconds to make sure the hook is well embedded. Our salmon is now hopefully well hooked and we unclamp the fly line, ease off the pressure and play the fish.

A shorter version of the strategy outlined above would be – as we get the first tug drop the rod tip a little, as the tugs gradually get stronger we keep dropping the rod tip in gradual increments, when the tugs change into strong pulls stop dropping the rod tip clamp the line tight for a few seconds as we smoothly raise the rod back up as this sets the hook, then ease off and play the fish.

David Anglis stayed calm during the take, and hooked this nice fish on the Ridge pool River Moy

The main points to remember are – try to keep the rod tip well up as the fly fishes around, drop the rod tip in gradual increments as the tugs get stronger, when the gradually strengthening tugs change to strong pulls where you are really starting to feel the weight of the fish then clamp the line and smoothly raise the rod to set the hook. I get to see a lot of salmon hooked successfully or lost because of incorrect technique, but one of the most enjoyable hook-ups that I have witnessed in quiet a while happened as Andre Babik was fishing a pool on the Moy a few years ago. A salmon took Andre’s fly with a tug tug, Andre dropped his rod tip a little in response, but he had to wait about five seconds before he got another single tug and he dropped his rod tip a little more in response, then there was a lapse of about three or four seconds before he started to get a series of gradually stronger tugs, he continued to drop his rod tip a little with each successive tug and when the transition from gradually stronger tugs to strong pulls came he clamped the line and set the hook. The whole taking sequence took about eight to ten seconds, but Andre had the patience to remain calm and wait to claim his prize. The real secret is waiting until the tugs change to strong pulls, and as an experiment just hold the sleeve of your shirt with two fingers and have a few tugs, then grasp a good clump of your sleeve with all your fingers clenched tightly and have a few progresively stronger pulls, I hope you will feel the subtle difference between tugs and progressively stronger pulls.

All the best

Paddy